Disability and Assisted Suicide: Elucidating Some Key Concerns (Professor Tim Stainton)

Read in PDF

As euthanasia and assisted suicide (EAS) becomes more common and more permissive, disabled persons grow increasingly concerned about how this will negatively impact them. Long opposed to EAS, disabled persons’ organisations have raised a number of concerns. This paper explores some of the background and context of those concerns and examines a number of key issues and examples which suggest their fears are not unfounded. The eugenic targeting of disabled persons historically and contemporary examples of a modern ‘quiet eugenics’ are explored. This is followed by consideration of how certain strains of utilitarian ethic may not just permit, but encourage, the elimination of disabled persons. Public and health care attitudes towards disability and how that might influence EAS are then considered followed by consideration of more concrete concerns regarding suicidal ideation, feelings of burdensomeness and, adjustment to traumatic injury and how these may impact disabled persons with regards to EAS. The paper then considers a core concern regarding how the lack of disability supports and generally poor socio-economic outcomes of disabled people may lead to disabled people seeking EAS. Finally we consider the efficacy of safeguards and some potential concerns with regards to EAS and disabled persons. The paper concludes with a call to take the disabled community’s concerns seriously as we move to ever more common and permissive EAS regimes.

The disability community has long expressed concerns regarding euthanasia and assisted suicide (EAS). [1] The long-standing ‘Not Dead Yet’ [2] movement is perhaps the most widely known disability organisation opposed to EAS. Their concern is shared by the former UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities Devandas-Aguilar who, after a visit to Canada, was “extremely concerned” about the implications of ‘assisted dying’ legislation on people with disabilities. Similar concerns were raised by her successor Gerard Quinn. [3] The rapid rise in jurisdictions legalising or considering legalisation of EAS coupled with the increasing range of conditions and circumstances where EAS is permitted [4] has only heightened the concern and urgency of the disability community and others regarding EAS. While disabled individuals are as varied in their views on EAS as the general population, the vast majority of disability rights and related organisations have expressed grave concern over the specific threats EAS poses to disabled persons. This paper seeks to articulate the nature of those concerns and the broader context which underlies them.

Before we begin it needs to be acknowledged that disability covers a vast range of conditions from sensory impairments, physical and mental disabilities as well as a range of expressions from lifelong, traumatic, degenerative or episodic. To some degree the implications of EAS will vary across this range but for our purposes we will use the approach adopted by the UN Convention on the Rights Persons with Disabilities which emphasises the barriers disabled persons face in achieving full and equal participation in society [5] rather than specific impairments. [6]

To fully understand the disability concerns over EAS some historical context is useful. The eugenics movement of the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries was to a large degree focused on the control and in many cases, the elimination of those considered ‘unfit’. A strong and healthy society could not afford to accept or ignore the presence, let alone the procreation, of members affected by disabling conditions, both socially, physically, and intellectually [7] who became a primary target of eugenics inspired policy throughout Europe and North America. The eugenics movement reached its nadir with the Nazi Aktion T4 program, a precursor and testing ground for the wider holocaust to come. Aktion T4 led to the state-sanctioned and physician-led murder of some 300,000 people with disabilities, many on the grounds of ending suffering. [8] Hitler made his intention and target quite clear:

‘[The State] must see to it that only the healthy beget children… It must declare unfit for propagation all who are visibly sick or who have inherited a disease and can therefore pass it on… Those who are physically and mentally unhealthy and unworthy must not perpetuate their suffering in the body of their children… A prevention of the faculty and opportunity to procreate on the part of the physically degenerate and mentally sick… would not only free humanity from immeasurable misfortune, but would lead to a recovery which today seems scarcely considerable’. [9]

While tempting to dismiss this as simply part of the madness of National Socialism, it is important to note this was simply the extreme, and to some degree logical, outcome of eugenic beliefs widely held in the west including prominent figures such as Beveridge and Churchill.

Nor can we claim that similar beliefs do not still exist. In 2016, 26-year-old Satoshi Uematsu murdered 19 disabled people in the care home where he worked in Japan. In explaining his motives, he notes ‘I envision a world where a person with multiple disabilities can be euthanised, with an agreement from the guardians’. [10] In a letter he attempted to deliver to the Speaker of the Japanese House of Representatives he called for ‘a revolution’, demanding that all disabled people be put to death through ‘a world that allows for mercy killings’. And in a statement chillingly reminiscent of Hitler’s he states: ‘My reasoning is that I may be able to revitalise the world economy…’. [11]

While this extreme example may be easy to dismiss as a tragic act by a disturbed individual there are other examples of what has been termed the ‘new’ or the ‘quiet’ eugenics. [12] Current trends in pre-natal testing indicate a strong negative view towards having a child with a disability. [13] The potential to ‘eliminate Down’s Syndrome’ through pre-natal testing (PNT) and selective termination is now being discussed widely as a very positive development both with regards to the elimination itself and the potential cost savings which might be realised. [14] Disability scholars have argued that the practice expresses strongly negative views towards persons with disabilities generally and promotes negative attitudes towards those persons currently living with a disability. Further, it has been argued that these views are the product of a false and biased view about disabled lives as ones of inevitable suffering and that this suffering is inherent to the impairment itself rather than socially produced. [15]

A further area which suggests this negative valuation of disabled persons in health care is the practice of neo-natal euthanasia. Legal in Belgium and the Netherlands, evidence suggests it is widely practiced elsewhere despite being illegal. In 2002, the Groningen Protocol (GP) for neonatal euthanasia was developed in the Netherlands with the intent to regulate the practice of actively ending the life of newborns. Significant numbers of these cases involve neonates with non-life threatening, medically treatable conditions and disabilities. [16] The American College of Paediatricians note that there is much room for parental, physician, personal, social, and economic bias. In their review of all 22 cases reported to the district attorneys’ offices in the Netherlands from 1998-2005, Verhagen & Sauer found that all involved spina bifida. They report that the considerations used to decide on euthanising included: expectation of extremely poor quality of life (suffering) in terms of functional disability, pain, discomfort, poor prognosis, and hopelessness; predicted lack of self-sufficiency; expected hospital dependency; and, long life expectancy. What is striking here is that none of these cases were terminal nor apparently experiencing significant physical pain. In all cases these were largely third party, subjective determinations of perceived future quality of life. It is not an unreasonable proposition that similar consideration would influence the practice of EAS.

The idea that disability inevitably leads to a life of suffering and poor quality is a key belief that underpins the view that providing access to EAS for disabled persons is both a compassionate and, in many cases, the morally correct thing to do. This is most evident in, but not exclusive to, certain strains of Utilitarian ethics. Singer’s views about disabled persons moral status and the ethics of euthanasia are perhaps best known. [17] He is far from alone, however. John Harris writes with regards to prenatal testing and elimination of disabled foetuses that ‘where we know that a particular individual will be born “deformed” or “disfigured”… the powerful motive that we have to avoid bringing gratuitous suffering into the world will surely show us that to do so would be wrong’. He goes on to state that in the case of severe disability ‘we should give them a humane death by legalising euthanasia in such cases’. [18]

As Tuffrey-Wijne et al note: ‘the fact that the disability itself, rather than an acquired medical condition, can be accepted as a cause of suffering that justifies euthanasia is deeply worrying’. [19] Where this becomes most concerning is when it is operationalised through approaches like Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) to determine what, if any, interventions offer the best cost-benefit outcome. Some bioethicists have endorsed the view that utilitarianism requires discrimination against the disabled in the allocation of health care resources based on the maximisation of quality adjusted life years. [20] As Hilliard states, ‘Consistent with the utilitarian ethic, state sanctioned killing of those deemed to have "lost their dignity" is hailed as a “good”’. [21] In the context of EAS, use of QALYs or similar methods raise some very serious concerns. As Barrie notes, ‘problems (with QALYs) relate closely to the debate over euthanasia and assisted suicide because negative QALY scores can be taken to mean that patients would be “better off dead”’. [22]

Gill in her review of evidence regarding physician attitudes towards disability and the impact on treatment decision found that health professionals tend to hold a negative view regarding the quality of lives of disabled persons and often more negative than that of the general public. She further notes that ‘Research has shown for some time that many health professionals believe life with extensive disabilities is not worth living’. [23] A recent study out of Harvard which surveyed 714 practicing US physicians found that 82.4 percent reported that people with significant disability have worse quality of life than non-disabled people. They note ‘these findings about physicians’ perceptions of this population raise questions about ensuring equitable care to people with disability. Potentially biased views among physicians could contribute to persistent health care disparities affecting people with disability’. [24]

There is an extensive literature, along with copious anecdotal reports, regarding negative experiences with the health care sector by persons with disability. These range from physical impediments to attitudinal barriers to reluctance / refusal to provide treatment, refusal of transplants, failure to undertake treatment that would normally be offered to a non-disabled person or undertaking non-medically necessary, highly invasive and high-risk interventions. [25] All of these suggest unbiased practice of EAS with regards to disabled individuals is highly questionable.

While there are certainly disabled people who suffer due to their impairments, the evidence does not support the view that this is inevitable or results in lower quality of life. Angner and colleagues examined the relationship between health and happiness. While they only examine mild chronic pain and various co-morbidities (such as asthma, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease), they determined that the only negative relationship between health and happiness occurs in the immediate period following the onset of symptoms or the rendering of a diagnosis. After an adjustment period, however, they learned that happiness and well-being return to approximately the same levels as previously identified by the individual. [26] Another study on adjustment to spinal cord injury notes that the degree of participation is a significant factor in adjustment [27] which would support the notion that it is less the impairment itself than the social impacts which reduce quality of life.

Albrecht and Devlieger have coined the term ‘disability paradox’ for the contrasting view of non-disabled and disabled persons with regards to quality of life with a disability as many with persistent and serious disabilities report that they experience anywhere between a good to an excellent quality of life. The authors suggest that this discrepancy between disabled and non-disabled perspectives highlights the significance of personal experience, individual self-determination, and social relationships. [28] Without these, non-disabled persons can make wrong, and in the context of EAS, serious assumptions about the quality of disabled persons’ lives.

The above concerns can be seen in attitudes towards suicide. In a study involving 500 individuals in the US surveyed on attitudes towards the acceptability of suicide when a disability is present, Lund et al found that suicide was generally viewed as more acceptable when the person had a disability. They note in their conclusion that these results not only provide insight into general attitudes towards disability but also may have clinical implications. They suggest that individuals with disabilities who are experiencing suicidal ideation may receive a social message that ‘their disability makes suicide more acceptable or understandable, they may feel that they have implicit social permission to commit suicide; in other words, the message of “suicide is not an option” could instead be conveyed as “suicide is not an option for everyone, but it is an option for you”’. [29] Evidence from Canada would seem to support this view where there have been several cases of individuals being advised that EAS is now an option for them despite having expressed no desire to consider this. [30]

A key concern of the disability community is that people will seek access to EAS because they are unable to secure the degree or types of disability supports and accommodations they need to live a full and meaningful life. The question of whether disability inevitably involves suffering as discussed above leads to another question which is rarely addressed in EAS considerations: that of causation. A disabled person may be suffering and subjectively indicate that is the case which would qualify them for EAS in some jurisdictions. This general view that disability will inevitably involve suffering leads to an uncritical acceptance of the professed suffering, but fails to ask the critical question of what are the actual causes of the suffering.

Numerous cases are now on record where disabled individuals are clear that they are seeking EAS because they are only offered the option of institutionalised care which they feel is incompatible with a life of dignity and of a quality they feel is acceptable. Archie Rolland died by EAS in 2016. A press report at the time noted: ‘It’s not the illness that’s killing him, he’s tired of fighting for compassionate care’. [31] M. Truchon noted it is the nature of the care he is being offered which is, at least in part, behind his suffering: ‘At a news conference… Mr. Truchon had an assistant read a statement explaining that he couldn't face the prospect of life confined to an institution’. [32] 41-year-old Sean Tagert, a man with motor neurone disease / ALS, died by EAS in August of 2019. He was quite explicit that his reason for choosing assisted death was his inability to secure sufficient home care funding in order live a life he considered worth living. [33] All he wanted was to remain in his home which had the necessary adaptations and to be able to spend time with his young son in their home. As sufficient home care hours were not offered, he chose death over institutionalisation.

The testimony of Jonathan Marchand to the Canadian Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs powerfully sums up the situation many disabled persons find themselves confronted with:

‘I was prepared to do anything to get out of this medical hell, but just like Jean Truchon, I was denied the home care support that I needed… After two and a half years in the hospital, I ended up in a long-term care facility… I gave up and sank into depression. I was ashamed to live in this ghetto. Without humanity and freedom, life no longer has any meaning. I regretted having refused euthanasia. I simply wanted to live with my partner, work and have a normal social life. I wanted to die. … My disability is not the cause of my suffering, but rather the lack of adequate support, accessibility, and the discrimination I endure every day… Why is it so hard to be seen and heard when we want to live?’ [34]

Overall, best practice in the field strongly supports maximum independence and control over disability supports through direct funding and home-based supports. There is no reason inherent to the disability that anyone cannot be supported in a suitably adapted home. The reason disabled people are institutionalised is largely structural, based not on best practice or the needs of the individual but on outdated policy and imagined financial savings. Access to community supports, even if sufficient supports are available, is usually met with significant delays. Delays which in the context of EAS can be deadly as the above citations suggest.

While many of the EAS related cases are concerned with inappropriate institutionalisation as the source of suffering, those not faced with this choice at the moment struggle against multiple socio-economic barriers. Income, poverty and employment outcomes for disabled people across jurisdictions are consistently and dramatically well below those of the general population. [35] People with disabilities, particularly women, are also far more likely to be victims of violence. Add to this poor access to appropriate housing and poor access to disability supports, the general picture of being disabled is not one conducive to living a full and meaningful life. Suicide and suicidal ideation are strongly correlated with socio-economic deprivation. [36] A recent study on suicide and disability notes that while rates are higher than the general population this can in part be explained by social adversity, including food insecurity and low sense of community belonging. [37]

The lack of appropriate supports also creates an increased reliance on family and friends to provide support. Feelings of burdensomeness observed in persons with disabilities has been associated with suicidal ideation or attempts. [38] Data from Oregon shows that 54.2% indicate being a burden on family, friends/caregivers as a reason they have sought to end their lives. [39] As above, this is to a large degree a function of the presence or absence, and the adequacy, of disability supports.

More critically with regard to the issue discussed above, current EAS regimes such as the current Canadian legislation, include little or no requirement for meaningful psycho-social assessment of the person’s situation and what may be leading to their request for EAS. Additionally little attention is paid to, and there is no requirement to provide, support alternatives that would lessen the ‘suffering’.

While the cases noted above seem to indicate the lack of acceptable care options is a major impetus in seeking EAS, the general social position of many disabled persons can also lead to a life of struggling. The risk of opting for EAS, rather than continuing to struggle against the many barriers disabled persons face in trying to live a meaningful and fulfilling life, is not one that can be lightly dismissed. This risk is arguably heightened in the context of austerity and concern with rising health and social care cost.

Most advocates for EAS will argue that with stringent safeguards EAS will not present a risk to vulnerable or disabled persons. There are now a broad range of EAS regimes, from relatively restrictive regimes where EAS is generally available to those clearly at the end of life, to more liberal regimes such as the Netherlands, Belgium and Canada where EAS is more broadly available well beyond those at the end of life. While all jurisdictions will present some risk to disabled persons, those where death is not required to be relatively imminent present a significantly greater risk for the reasons detailed above. At particular risk are those who have suffered a traumatic injury. Adjustment to a traumatic injury resulting in disability can take a significant amount of time, but most do adjust, and both suicidal ideation and assessment of one’s quality of life changes for the better over time. If EAS is available during the immediate post-injury phase, then it is highly likely many will choose EAS, whereas given time to adjust many would likely choose to live.

The consent requirement is another key safeguard cited by proponent of EAS. While it clearly offers some protection this cannot account for subtle pressure or unconscious bias that may encourage consent. Tuffrey-Winje et al [40] writing in regards to a number of cases for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities euthanised in the Netherlands note: ‘We found no evidence of safeguards against the influence of the physicians’ own subjective value judgements when considering EAS decision, nor of processes designed to guard against transference of the physicians’ own values and prejudices’. Eligibility for EAS usually involves an evaluation of ‘suffering’ which as noted above, is often uncritically directly associated with disability. They also note their analysis of the data raises serious concerns about both the difficulties in assessing whether the patient had made a ‘voluntary and well-considered request’, which as they note, is closely linked to an assessment of the patient’s decision-making capacity, and the stringency of the assessments used to make the above determinations. These findings are particularly worrying as EAS is extended to persons with cognitive impairments.

Finally, safeguards, even at their best, are not necessarily permanent. As we have seen in a number of jurisdictions, there is a tendency for EAS regimes to move towards ever more liberal application – the ‘slippery slope’. [41] So what is initially a fairly restrictive approach can rapidly become a far more liberal, and with regards to disabled person, a far more dangerous regime. [42]

As EAS regimes expand to include those with cognitive impairments and move away from explicit contemporaneous consent through vehicles like advance directives, it is not beyond imagining that guardians and parents may be extended the right to consent to EAS on behalf of their disabled children. The all-too-prevalent filicide of disabled children and the rather sympathetic response such cases often garner, being framed as ‘mercy killings’, suggests there would be significant public support for the practice. [43] It is also not inconceivable that families with decision-making control or influence will choose EAS for their children when faced with insurmountable barriers to securing appropriate supports.

While the expansion of EAS has been motivated by a desire to end suffering and respect autonomy, in doing so we have created significant risk to disabled persons in a world which largely sees their lives as less valuable, as ones of inevitable suffering and as not worth living. As more and more jurisdictions consider allowing or expanding EAS, it is critical that we take into account the very real concerns of the disability community and in our desire to expand the autonomy of the many, we do not trample on the rights of disabled persons to live, and to live a life of quality and equity.

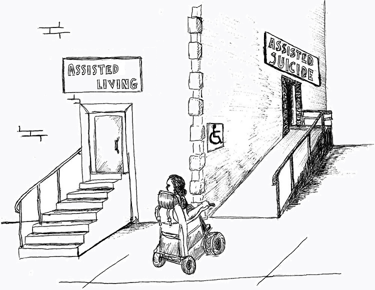

The cartoon accompanying this briefing is an adapted version of that created by Amy Hasbrouck, a Board Member of Not Dead Yet in the US, and Director of Toujours Vivant-Not Dead Yet, a project of the Council of Canadians with Disabilities to expand the reach of their Ending of Life Ethics Committee. The original picture may be found here.

[1] For more on definitions see Jones DA (2021). ‘Defining the terms of the debate: Euthanasia and euphemism’, Briefing Papers: Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide. Oxford: Anscombe Bioethics Centre.

[2] ‘Not Dead Yet’ is a global network of disabled persons’ organisations dedicated to opposing EAS. https://notdeadyet.org/

[3] Ms Catalina Devandas-Aguilar, on her visit to Canada (2019, 12 April). End of Mission Statement by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner; Evidence of Gerard Quinn (01 February 2021). United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, United Nations Human Rights Council, Senate, Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Evidence, 43-2 6.

[4] Spain, New Zealand, Canada, all six Australian States are some of the recent jurisdictions legalising EAS in one form or another. Key areas where jurisdictions have expanded the scope of EAS include removal of the requirement that the person be at the end of life, access by persons with dementia, or mental illness, mature minors and removing the need for contemporaneous consent.

[5] Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others. (CRPD Art. 1)

[6] The issue of mental illness and EAS raises a number of unique issues and deserves a fuller treatment than can be provided here, though much of what is contained in this paper applies to mental illness.

[7] Hawkins M (1997). Social Darwinism in European and American thought 1860-1945: Nature as model and nature as threat. London: Cambridge University Press.

[8] Hohendorf G (2016). ‘Death as a release from suffering—The history and ethics of assisted dying in Germany since the end of the 19th century’, Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research, 22, (2), 56-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npbr.2016.01.003. See also Rubenfeld S and Sulmasy DP (eds.) Physician-Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia: Before, During, and After the Holocaust (Washington DC: Lexington books, 2020).

[9] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1943), pp. 403-4.

[10] Willitt P (2016). Disability Hate Leads to Mass Murder in Japan, Global Comment.

[11] Police search home of suspect in Japan stabbing spree. Associated Press, 27 July 2016.

[12] Reinders, J, Stainton, T, and Parmenter TR (2019). ‘The Quiet Progress of the New Eugenics. Ending the Lives of Persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities for Reasons of Presumed Poor Quality of Life’, Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 16: 99-112. doi:10.1111/jppi.12298

[13] Skotko BG (2009). ‘With new prenatal testing, will babies with Down syndrome slowly disappear?’, Arch Dis Child 94 (11). 823-826.

[14] Quinones J & Lajka A (2017, 14 August). “What kind of society do you want to live in?”: Inside the country where Down syndrome is disappearing. CBC News.

[15] See: Parens E & Asch A (2003). ‘Disability rights critique of prenatal genetic testing: Reflections and recommendations’. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 9(1), 40-47.

[16] Verhagen E & Sauer PJ (2005). ‘The Groningen Protocol — euthanasia in severely ill newborns’, English Journal of Medicine; 352(10), 959-962; American College of Paediatricians. Neonatal Euthanasia: The Groningen Protocol (2004).

[17] Singer has consistently express his views on the morality of killing disabled persons and the relative moral status of some disabled persons and certain animals. See Singer P. Practical Ethics, 2nd edition, Cambridge: CUP. 1993, pp. 175-217; Singer P. Animal liberation, New York, NY.

[18] Harris J (1998). Clones, genes, and immortality: Ethics and the genetic revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[19] Tuffrey-Wijne I, Curfs L, Finlay I, Hollins S. (2019). ‘“Because of his intellectual disability, he couldn’t cope”. Is euthanasia the answer?’, Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 16: 113-116. doi:10.1111/jppi.12307.

[20] McKie J, Richardson J, Singer P, Kuhse H. (1998). The allocation of health care resources: An ethical evaluation of the ‘QALY’ approach. Aldershot, England; Brookfield, USA: Ashgate. 29. Stein MS. (2001) ‘Utilitarianism and the disabled: distribution of resources’. Bioethics. 16(1), 1-19.

[21] Hilliard MT (2011). ‘Utilitarianism Impacting Care of those with Disabilities and those at Life’s End’. Linacre Q. 78(1):59–71. doi:10.1179/002436311803888474.

[22] Barrie S (2005). ‘QALYS, euthanasia and the puzzle of death’. Journal of Medical Ethics. 41,635-638.

[23] Gill CJ (2000). ‘Health professionals, disability, and assisted suicide: An examination of relevant empirical evidence and reply to Batavia’. Psychology, Public Policy and Law. 6; 2, 526-545.

[24] Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Agaronnik ND, Donelan K, Lagu T, Campbell EG (2020). ‘Physicians’ Perceptions of People with Disability and their Health Care’, Health Affairs. 40(2):297-306. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452. PMID: 33523739.

[25] See: Gill, 2000; Drainoni ML, Lee-Hood E, Tobias C, Bachman S (2006). ‘Cross-disability experiences of barriers to health-care access: Consumer perspectives’. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 2006; 17(2), 101-115. See: Diament M (2016, 24 October). ‘Disability no reason to deny organ transplants, lawmakers say’. Disability Scoop; Pilkington E, McVeigh K (2012). ‘‘Ashley treatment’ on the rise amid concerns from disability rights groups’, The Guardian.

[26] Angner E, Ray MN, Saag KG, & Allison JJ (2009). ‘Health and Happiness among Older Adults: A Community-based Study’. Journal of Health Psychology 14, no. 4 503-512.

[27] Erosa NA, Berry JW, Elliott TR, Underhill AT, Fine PR. (2014) ‘Predicting quality of life 5 years after medical discharge for traumatic spinal cord injury’, British Journal of Health Psychology. 19(4):688-700. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12063. Epub 9 Aug. 2013. PMID: 23927522.

[28] Albrecht GL and Devlieger PJ (1999). ‘The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds’. Social Science & Medicine, 48: 977-988.

[29] Lund EM, Nadorff MR, Winer ES, & Seader K (2016). ‘Is suicide an option?: The impact of disability on suicide acceptability in the context of depression, suicidality, and demographic factors’. Journal of Affective Disorders, 189, 25-35.

[30] Chronically ill man releases audio of hospital staff offering assisted death. CTV News (2018, 02 August); Mother says doctor brought up assisted suicide option as sick daughter was within earshot. CBC News (2017, 24 July).

[31] Fidelman C (2016, 27 June). Life in long-term hospital “unbearable”: Montreal man with ALS. Montreal Gazette; Testimony of Jonathan Marchand, Senate, Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Evidence, 43-2 (01 February 2021), online: https://sencanada.ca/en/Content/Sen/Committee/432/LCJC/10ev-55128-e

[32] Tu Thanh Ha (2017, 14 June). Montrealers file civil suit over assisted-dying laws, Globe and Mail.

[33] B.C. man with ALS chooses medically assisted death after years of struggling to fund 24-hour care, CBC News (2019, 13 August).

[34] Testimony of Jonathan Marchand, Senate, Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Evidence, 43-2 (01 February 2021), online: https://sencanada.ca/en/Content/Sen/Committee/432/LCJC/10ev-55128-e

[35] United Nations. Factsheet on Persons with Disabilities, accessed 2022, 02 February; Office of National Statistics (UK) Outcomes for disabled people in the UK: 2020. (Release date: 2021, 18 February); Morris S., Fawcett G., Brisebois L., Hughes J., Canadian Survey on Disability Reports: A demographic, employment and income profile of Canadians with disabilities aged 15 years and over, 2017. Statistic Canada. (Release date: 2018, 28 November).

[36] See: Curtis B, Curti, C, & Fleet RW (2013). ‘Socio-economic factors and suicide: The importance of inequality’. New Zealand Sociology, 28 (2), 77-92; Burrows S, Auger N, Roy M, & Alix C (2005) ‘Socio-economic inequalities in suicide attempts and suicide mortality in Québec, Canada, 1990–2005’. Public Health, 124 (2), 78 – 85.

[37] McConnell D, Hahn L, Savage A, Dubé C, Park E (2016). ‘Suicidal Ideation Among Adults with Disability in Western Canada: A Brief Report’. Community Mental Health Journal. 2016 Jul;52(5):519-26. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9911-3.

[38] Russell D, Turner RJ, & Joiner TE (2009). ‘Physical disability and suicidal ideation: A community-based study of risk / protective factors for suicidal thoughts’. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 39 (4), 440-451; Khazem LR, Jahn DR, Cukrowicz KC, & Anestis MD (2015). Physical disability and the interpersonal theory of suicide. Death Studies, 39 (10), 641-646.

[39] Oregon Death with Dignity Act Data Summary (2021). Oregon Health Authority.

[40] Tuffrey-Wijne I, Curfs L, Finlay I, Hollins S (2018). ‘Euthanasia and assisted suicide for people with an intellectual disability and / or autism spectrum disorder: an examination of nine relevant euthanasia cases in the Netherlands (2012-2016)’. BMC Medical Ethics. 19(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12910-018-0257-6

[41] See Keown J (2021). ‘Voluntary Euthanasia & Physician-assisted Suicide: The Two ‘Slippery Slope’ Arguments’. Briefing Papers: Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide. Oxford: Anscombe Bioethics Centre.

[42] Canada for example, despite initial claims to robust safeguards and claims there was no slippery slope, has in four years since the passage of its initial EAS legislation which restricted access to those whose death was reasonably foreseeable, excluded mental illness, and required contemporaneous consent, now has reversed course on all three elements, giving it one of the most permissive EAS regimes in the world.

[43] See for example: Picciuto E (2014, 04 November). U.K courts grant mother right to end her 12-year-old disabled daughter’s life. The Daily Beast; Perry D (2017). On media coverage of the murder of people with disabilities by their caregivers. Rudderman Foundation; Joni Eareckson Tada (2012, 27 June). Disappointed in Dr Phil, Huffington Post; Coorg R & Tournay A (2012). ‘Filicide-Suicide Involving Children With Disabilities’. Journal of Child Neurology 28(6) 745-751.

Most recent

A Human Right to Suicide Prevention: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill III’

03 June 2025

An Equal Opportunity to Live: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill II’

03 June 2025

Ending Life as Cutting Costs: Analysis of ‘The Impact of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill I’ (Professor David Albert Jones)

23 May 2025

Support Us

The Anscombe Bioethics Centre is supported by the Catholic Church in England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, but has also always relied on donations from generous individuals, friends and benefactors.